Original publication here: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2025.105986

Dec 2025

K.M. Gonzalez, W.R. Matias, A.M. Mohareb, D. Sridhar

Abstract

Objectives

Study design

Methods

Results

Conclusions

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

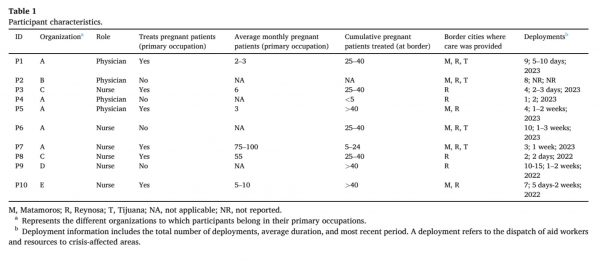

2.2. Sampling and participant recruitment

2.3. Data collection

2.4. Data analysis

2.5. Reflexivity

3. Results

3.1. Theme 1: Structural violence

3.1.1. Denial of care

Participants described how migrants were frequently turned away from hospitals without evaluation, received incomplete diagnostics, or were denied ambulance transport and admission. Routine PNC through state systems were often inaccessible due to financial barriers, and even those who delivered in hospitals were discharged quickly without postpartum care.

“Some people just flat out get turned away. Or there were situations where we would send someone to the hospital … and they didn’t even do the workup … At the public hospital, my understanding is [that] care should be free, but a lot of times you have to provide your own supplies and purchase [your own] medicines. – P1

3.1.2. Discrimination and language barriers in healthcare access

Language barriers and racial discrimination, particularly against Haitian migrants, were cited as major obstacles within Mexican healthcare institutions.

“The Haitian population [is] really discriminated against and not provided care [for]. [Hospitals are] just churning Haitians away or [providing] basic care and then turning them away. – P7

3.1.3. Cartel violence and safety concerns

Fear of cartel violence deterred migrants from accessing local services. Participants noted that unsafe conditions—such as pregnant women being unable to walk unattended—compromised their sense of safety, which may adversely affect maternal health.

“I learned about the drug cartels there … They’re patrolling the streets and it’s hard to know who is who. So, for a pregnant woman to walk the streets unattended, [it] can be dangerous.” – P4

3.1.4. Overburdened public health system

Participants emphasized that the Mexican public health system was already under strain and faced additional pressure in responding to the needs of the migrant population.

“They’re already taking care of very destitute groups of Mexicans [and] are also expected to handle this new influx of migrants.” – P6

3.2. Theme 2: Resource limitations

3.2.1. Shortage of specialized providers

Participants noted a significant lack of specialists, particularly obstetricians and gynecologists. Most providers were generalists, and many participants reported working beyond their usual scope of practice, gaining experience through their clinic work at the border.

“This is not my area of expertise at all … I don’t have the kind of comprehensive knowledge of what to expect at a particular stage of pregnancy or what normal [is]. What [is] abnormal? That was all learned throughout my time in the clinics.” – P6

3.2.2. Limited medical supplies and diagnostic equipment

All participants described limitations in available supplies and diagnostic equipment. While basic labs and limited ultrasounds were accessible, budgetary constraints and reliance on external referrals restricted comprehensive screening for infections, congenital anomalies, and fetal growth.

“So that a pregnant woman was getting regular exams, ultrasounds, lab[s] … That kind of care is just not possible to maintain.” – P6

3.2.3. Lack of privacy in makeshift clinics

Participants noted that GRM clinics operated in makeshift spaces—such as courtyards, dining halls, or porches—where limited privacy impeded the ability to address sensitive issues like gender-based violence (GBV) or perform sexually transmitted disease (STD) screenings.

“We weren’t screening for STDs. No, because that means undressing them … There’s really no privacy in those clinics.” – P7

3.3. Theme 3: Care fragmentation

3.3.1. Patient mobility disrupts follow-up care

Participants identified the mobile nature of the migrant population as a major barrier to continuity of care. Migrants frequently moved between cities while awaiting asylum or seeking safety or resources, sometimes traveling over 50 miles to access services.

“That person either crosses over or something happens to them, they disappear. You don’t know what happens to them … That’s not an element [that] can be accomplished there.” – P5

3.3.2. Short-term staffing reduces provider continuity

The use of short-term, rotating volunteers made it difficult for patients to see the same provider across visits. Participants noted that this disrupted continuity of care and hindered relationship-building and consistent follow-up.

“If we wanted to see [a patient] the following week, chances are they were going to see a different [provider] … You’re writing notes in their little prenatal book, hoping that the next person can pick up where you left off.” – P4

3.3.3. Fragmented medical records hinder clinical decision-making

Participants explained that inconsistent medical records hindered effective follow-up and care planning. Key clinical data—such as pregnancy history, group B streptococcus (GBS) status, and prior complications—were often unavailable. Several participants expressed concern about tracking preeclampsia, which they noted was particularly common among Haitians, who comprised the majority of GRM’s patients.

“Part of prenatal care is pregnancy history. If someone has a history of pregnancy loss, that’s a very important indicator for the current pregnancy.” – P5

4. Discussion

4.1. Conclusion

This study reveals an escalating humanitarian crisis at the US–Mexico border, where basic PNC remains out of reach for pregnant migrants. Structural violence, resource limitations, and care fragmentation undermine the quality and accessibility of maternal healthcare. Despite the efforts of humanitarian organizations, entrenched systemic barriers persist. Addressing these challenges will require comprehensive policy reform, strategic resource allocation, and coordinated binational action grounded in human rights. Strengthening integration between NGOs and formal healthcare systems could enhance service coordination, equity, and outcomes for underserved border communities.48 Future research should incorporate the perspectives of Mexican healthcare providers and migrant communities, using community-based participatory approaches to develop rights-based, responsive models of care that bridge the gap between inclusive policy frameworks and on-the-ground healthcare delivery.36

Author statements

Ethical approval

Data availability

Author contributions

Funding

Competing interests

Acknowledgements

References: References Public Health Vol. 249