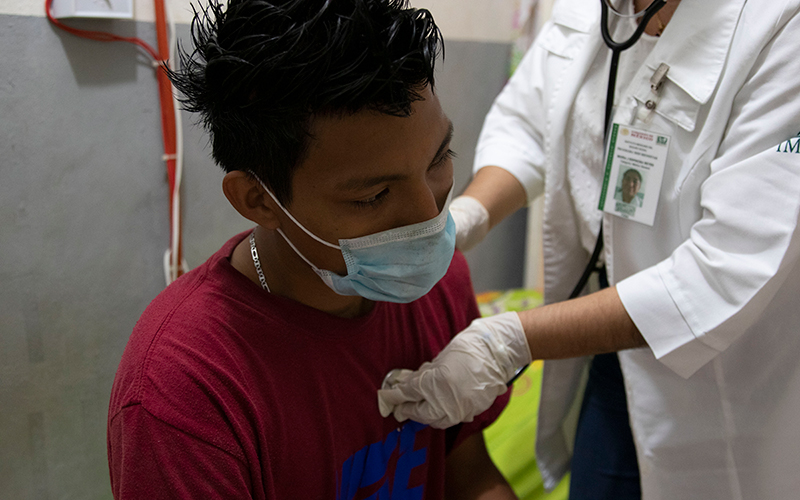

Lastly, with assistance from the federal programs IMSS-Bienestar and Grupo Beta, Jiménez and his team have assured that most every shelter in Tapachula has some level of medical staffing and transport to hospitals when necessary.

Despite these steps, some gaps remain.

Herbert Bermudez, a worker at Albergue Jesús El Buen Pastor, said he sometimes uses his own money to buy medicine for migrants who can’t find what they need in the shelter’s supply of donated medications.

In addition, COVID-19 continues to be a challenge in many shelters, creating staffing shortages and safety concerns because of overcrowding, which forced some to shut down, UNICEF reported in late March.

Jiménez acknowledged that it was difficult at the beginning to treat so many people from so many cultures, but said they’ve come a long way.

“I do not think I know perfection, but I think that we are already getting to know each person: the migrants from different countries,” he said.

But he also expressed long standing frustrations.

In his experience, Jiménez said, Haitians in particular are constantly in conflict with those who’re trying to help them, always pushing to the front of the line. He wants everyone to follow the system laid out for them and go through proper channels.

Jiménez also said migrants prioritize their health after everything else, especially immigration appointments and their attempts to leave Tapachula.

“More than anything, you need to know how the migrant puts other things first,” he said. “The least important of those things is their health.”

Benitez at Global Response Management also spoke to this phenomenon, although with a differing perspective.

“There’s a lot of people who need medical attention or psychological help, but they have other priorities,” she said. “Even if they know they need it (medical care), they prefer to go look for a job or make money to feed their family.”

More support needed

President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (referred to as AMLO) addressed the inefficiencies in this web of health care in a large-scale reform of Mexico’s health care system in early 2020. Healthcare reform was a major talking point of his campaign in 2018.

Although the strengths and weaknesses of the old system, known as Seguro Popular, were nuanced, it did guarantee asylum seekers three months of free health care access once they had their asylum appointments.

AMLO’s government created a fully public option, known as INSABI, to make health care more accessible for all, including migrants. Public funding was expanded by 35% in 2020 to meet these goals. That ended the three month limit for asylum seekers and expanded access, on paper anyway.

But communications about policy and expectation remain poor, according to some medical researchers, and there are widespread accounts of medication shortages and access issues for migrants and Mexican citizens alike. In addition, there have been reports of corruption within hospitals, which, when supplies are low, may charge patients for resources that should be free.

Experts also have criticized López Obrador for severely underfunding health care. An independent analysis in 2020 indicated health care in Mexico is under-resourced by as much as 658.5 billion pesos. And despite some funding increases, that gap hasn’t been closed.

Although the Chiapas health ministry contributes resources for migrants, the majority of the funding Jiménez distributes comes from NGOs. Jiménez is proud of the strides his team has made, but more support is needed, he said.

Jiménez said the NGOs he works closely with would soon be petitioning AMLO, who visited Tapachula on March 11, asking that “more resources be allocated to the health system.”

Benitez agreed that resources from the Mexican government have been lacking.

“The government doesn’t do enough,” she said. “That’s why it’s important that we NGOs are here.”

Government reforms have also been affected by the ongoing pandemic. Mexican public hospitals, which serve people who need more than basic care, often have found themselves overwhelmed, and wait times in emergency rooms remain high.

Furthermore, private and specialized treatment is beyond the financial reach of many migrants.

Caught in these currents are migrants like Karla Matute, the Honduran mother who sought help for her son’s injured arm.

At the clinic, a doctor put a more durable wrap on Joryí’s arm and referred him for an X-ray at the local hospital. Matute said the arm likely isn’t broken – Joryí would be in more pain if it were – but it’s worth checking to be sure.

They left the clinic with painkillers, but instead of heading to the hospital, Matute went to the National Immigration Office (INM). The night before, she had heard the agency might be giving humanitarian visas to the single mothers with children who’ve been sleeping in the park.

For the moment, anyway, Joryí’s arm will have to wait.

She’s hoping to leave soon and make her way north to Monterrey, where she heard there is work.

Additional reporting was contributed by Jennifer Sawhney, Juliette Rihl and Salma Reyes. Translations were done by Jennifer Sawhney and Salma Reyes.