November 11, 2024

Original article by Karen Miller-Medzon for WBUR published HERE.

The war in Ukraine is heading into its third winter, stretching the battered health care system to its breaking point. The World Health Organization’s last tally in August counted 1,940 attacks on health care facilities and 34 health care workers killed in the first eight months of this year, 10 more than in all of 2023. That’s in addition to injured and conscripted health care workers, rolling blackouts, failing equipment and a profound toll on mental health.

Among the organizations working to bolster and rebuild the country’s medical systems is Global Response Medicine, an NGO on the ground in Ukraine and other war zones. The organization develops battlefield-to-rehab care protocols and trains health care workers in the systems and procedures they need to practice wartime medicine.

Recently, GRM brought a group of Ukrainian health care workers to Boston Medical Center’s Solomont Simulation Center.

Inside the center, Dr. Joseph Leanza points a scalpel at a rack of pork ribs on a silver surgical table. Draped across a patient bed on the other side of the hospital-style room is an eerily life-like mannequin staring straight up at the fluorescent lights. On another table lies what appears to be an armless torso. It all looks a little like the set of a high-tech horror movie.

But that illusion is broken by a dozen Ukrainian health care workers — doctors, nurses, residents and a hospital director — crowded around Leanza, waiting to try out procedures and equipment that can help improve patient care in Ukraine.

Leanza — an emergency medicine doctor at BMC — is also the medical director for GRM which brought the health care workers to Boston from hard-hit cities including Kyiv, Kharkiv and Izyum. He’s guiding the group through ultrasound-assisted intubations, central line placement and more.

Of course, some of the demonstrations — no less important on the battlefield — are a little less high-tech, including surgical procedures on slabs of pork ribs purchased that morning at a local grocery store.

“They set them up as a sort of analog of the chest wall,” Leanza explains. “If someone has a gunshot wound or a stab wound to the chest, sometimes too much blood or too much air accumulate in the chest… and evacuating the blood can be the only necessary component to saving someone’s life.”

Among the Ukrainians digging in is Kharkiv doctor Vadym Serdiuchenko, who inserts his scalpel gingerly into the ribs, but turns quickly to Leanza to ask about how deep to go. Leanza suggests going “through the muscle, into the intercostals.”

Serdiuchenko says through a translator that this is the kind of practice and training he can’t get in Ukraine in wartime.

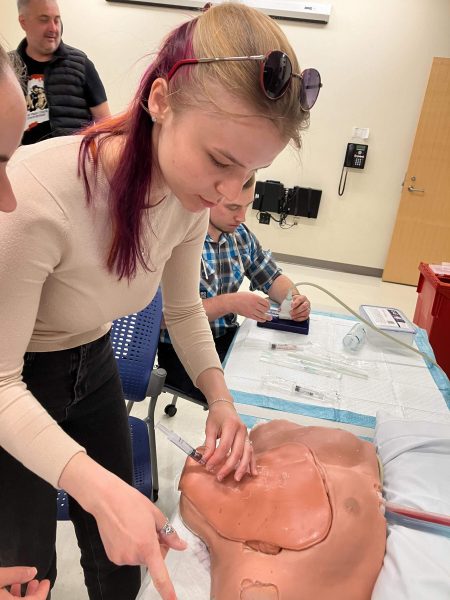

Across the room, also laser-focused on her task, is Viktoriia Totkalova. She’s using ultrasound guidance to insert a needle into an anatomically correct neck and torso. BMC ultrasound fellow Noelle Bates carefully guides her through the central line placement, a very skilled and potentially dangerous procedure.

“In a warzone, if somebody needs rapid fluid administration, this would be a way to go,” Bates explains.

Susanna Aksenkova is a second-year intensive care unit resident in Kharkiv where hospitals are being rebuilt even as the bombs are still falling. She says she and her mother — her only family — are from the Donbas region. But when shelling got too intense there at the beginning of the war, her mom left Ukraine. Aksenkova, just beginning her training, opted to stay in Kharkiv.

“In Ukraine, and especially in Kharkiv, we have a lot of critical patients with a blast injury,” she says. “So, we need to improve our knowledge and our system to give better medical treatment for them.”

She’s grateful for any opportunity to gather very specific skills that match the overwhelming need she sees in her hospital.

“I mean that for the patients, it’s really important,” she says, “like how deep you need to use your central line, how you need to fixate it, and extra materials you need for this procedure.”

Aksenkova continues, “Sometimes it’s difficult to do it in Ukraine because we don’t have enough equipment for a lot of procedures. And sometimes it’s really useful just to ask much more competent people and doctors how you can do it with such kind of equipment, which we have now.”

She goes on to explain the dismal state of medical care in her city.

“Nowadays, we don’t have enough medical staff. We don’t have enough doctors, we don’t have enough nurses,” Aksenkova says. “So, I truly can say that as a resident now we do almost the same as the MD.”

“It’s not so good because we don’t have enough clinical experience,” Aksenkova admits, but says she is still relieved to have stayed behind after her mother left, because, “I think I can help people right now in Kharkiv, and that’s important.”

Bohdan Berezhnyi has been listening quietly. He’s an anesthesiologist and the medical director of Izyum’s hospital, about 45 miles from the Russian front. His city spent more than six months under Russian occupation.

“Our hospital was destroyed at the beginning of war,” he says. “It’s a very sad story… If there is a war in your city, you haven’t electricity, you haven’t water, you haven’t heat, you cannot even walk to the street because a lot of the explosions.”

He explains that doctors were forced to hide on the ground floor of the hospital because attempting to go home was too risky.

“The emergency system didn’t work. You cannot call to your friends, your medical staff to come in. You just stay in your hospital on the ground floor and you wait for the patient who just can’t even have the possibility to come to the hospital by themselves,” he says, referencing the fact that during heavy shelling, it’s not possible for ambulances to respond.

When asked whether people simply die on the ground, he answers, “I’m sorry. But yes.”

Berezhnyi tells one particularly poignant story about Izyum residents trying to flee by running and driving over the only bridge leading out of the city.

“Despite Russia targeting them, 30 people die on one side [of the bridge] and 30 on the other side,” Berezhnyi says. “A man tries to cross the bridge and he hears bullets. He turns on the ground, he feels pain in his abdomen part, but he stays in this condition by one day.”

The man was retrieved by family members on the second day, but it was still too dangerous to bring him to the hospital. Finally on the third day, he was brought in for treatment. Berenzhnyi says that the man survived, but that he was the exception. Berezhnyi says those bleak days left him eager for training like this one, which he hopes will mean saving more lives.

Among the things he’s learning from his stint with GRM, he says, is how to standardize systems so that every patient gets the same intake, evaluation and assessment at every level of treatment.

Of course, the equipment hasn’t gone unnoticed.

“Our doctors can’t even imagine about this equipment,” Berezhnyi laughs. “And I personally too! The CT scan and the ultrasound equipment and the ventilators. It’s very interesting to us.”

Despite what feels to these Ukrainian health care workers like a never-ending war, Berezhnyi says he’s optimistic about rebuilding the medical systems in Ukraine, partly because of NGOs like GRM that are partnering with his country to bolster skills, training and systems.

Aksenkova, who’s never practiced outside a warzone, thinks carefully before weighing in on whether she shares his optimism.

“Probably more ‘yes’ than ‘no’” she says, “because difficult times… can create strong people.”

She says that the world’s medical community is taking note of what Ukraine is able to do on the battlefield.

“I see it every time if we are talking, not only about the civilian medicine, but also talking about the military medicine,’Aksenkova says. “I see how the protocols are changing because of the Ukraine, not only for Ukrainian doctors, but also for doctors throughout the world because we can now treat such a kind of injuries with such a low amount of equipment.”

But the irony is not lost on her. She says that having a top-notch simulation center, great education and a more resilient medical system would have been better learning tools than teaching “all this in such a cruel way.”

Aksenkova adds, “But it’s working.

*****

Karyn Miller-Medzon produced and edited this interview for broadcast with Todd Mundt. Miller-Medzon adapted it for the web.

This segment aired on November 11, 2024.