November 6, 2025

Published on Psychiatrist.com – Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders, Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(6):25f04056

Joseph L. Bonvie, PsyD; Sofia E. Matta, MD; Serhii Andriichenko, MD; Ihov Slobodian, MD; Andrea Leiner, APRN; Yulia Brockdorf, RD; Theodore A. Stern, MD

Lessons Learned at the Interface of Medicine and Psychiatry

The Psychiatric Consultation Service at Massachusetts General Hospital sees medical and surgical inpatients with comorbid psychiatric symptoms and conditions. During their twice-weekly rounds, Dr Stern and other members of the Consultation Service discuss diagnosis and management of hospitalized patients with complex medical or surgical problems who also demonstrate psychiatric symptoms or conditions. These discussions have given rise to rounds reports that will prove useful for clinicians practicing at the interface of medicine and psychiatry.

This article is the result of a collaboration between Ukrainian clinicians, both uniformed and civilian, and Home Base (a partnership between Massachusetts General Hospital and the Boston Red Sox committed to healing the invisible wounds of war).1 In March 2025, Global Response Medicine, an organization focused on delivering and managing humanitarian aid worldwide, facilitated a reciprocal partnership between Home Base and the Ukrainian Ministries of Interior and Health. This initiative was designed to share evidence-based practices and clinical innovations in support of Ukrainian military personnel and their families.

This article seeks to illuminate a newly emerging form of combat stress, one shaped by the relentless and psychologically corrosive nature of modern drone warfare. If you have ever wondered what it is like to live under the threat of a drone attack or thought about how drone attacks differ from those of artillery fire or ground assaults or been uncertain about how to treat someone who has developed combat drone-related posttraumatic stress and anxiety, then the following case vignette and discussion should prove useful.

CASE VIGNETTE

Mr A, a 28-year-old active-duty Ukrainian soldier, was returning to his post when the ground beneath his feet suddenly gave way. He had been unaware of the Russian-operated drone that had dropped munitions onto him. A second strike followed seconds later as he lay wounded, having lost all motor function in his legs.

Although his uninjured comrades applied tourniquets to his legs to control the bleeding, evacuation was impossible, as reconnaissance drones remained overhead searching for targets. Mr A was left isolated, immobile, and exposed, as his comrades sought cover.

When one drone continued to drop ordnance on him, another drone hovered nearby and recorded his distress (pain, fear, and helplessness) for propaganda purposes over social media. Mr A endured 5 more drone assaults before losing consciousness. Left for dead, the attacks paused, and Mr A’s comrades attempted to evacuate him. However, a reconnaissance drone detected their movement and dropped additional munitions and an incendiary device. Upon regaining consciousness, Mr A extinguished the flames on his body with his hands, after which chemical munitions were dropped by the drone rendering him unconscious once again.

Mr A was evacuated 14 hours later, under the cover of night. His injuries included bilateral lower-limb burn-blast injuries with severe tissue loss and infections that required several amputations; these were traumatic for him. During Mr A’s recovery and rehabilitation, he watched footage of his attack circulating on social media, re-exposing him in vivid detail to the event, and now accompanied by streams of “likes,” unsolicited opinions, and voyeuristic commentary from a distant, virtual audience.

DISCUSSION

Why Are Drones Increasingly Used in Military Conflicts?

For the purposes of this article, the term drone refers to an unmanned aerial vehicle or unmanned aircraft system that is either remotely piloted or utilizes software for autonomous flight. Modern drone performance varies based on propeller configuration, intended purpose, flight range, and payload capacity.

While the US military employed drones extensively during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the commercialization of drone technology since the Global War on Terror (GWOT) has profoundly reshaped modern warfare on sea, air, and land. The proliferation of civilian drone platforms is fueled by their low cost, operational simplicity, and expendability, making them a potent force multiplier.2 Rapid advancements in tactical technology since Russia’s full-scale invasion into Ukraine in 2022 has effectively made Ukraine a battlefield laboratory that has re-engineered the methods and means of conducting warfare and their associated human consequences.3

The most commonly used drones in Ukraine are civilian short-range first-person view (FPV) multirotor copters, modified for tactical purposes. Pilots control these FPVs using virtual reality headsets, providing them with gamified situational awareness of the battlefield. As drone operators gain experience, they advance to more complex aerial missions and platforms. FPV drones typically engage targets by dropping munitions, such as mortar shells and grenades, or by performing kamikaze-style attacks, detonating on impact. A single exploding FPV drone can cost between $200 and $500, a small fraction of the price of guided artillery shells that are 10–15 times more expensive.4 In contrast, modern Russian battle tanks cost approximately $4 million each and can be effectively destroyed by a small number of these inexpensive drones. This stark cost disparity underscores a significant strategic shift in modern warfare, where affordable unmanned systems can deliver disproportionate battlefield effects.

Composed in large part of civilian volunteers—teachers, laborers, and students—who now constitute approximately 60%–75% of Ukraine’s current military force,5 the Ukrainian defense has rapidly integrated drone technology into its defense strategy and become a contemporary example of asymmetric warfare. Russia, anticipating a swift and decisive victory, was initially unprepared for this unconventional resistance. However, Ukraine’s operational success compelled Russia to adapt quickly, accelerating its own investment in and deployment of drone capabilities, thereby initiating an arms race in unmanned systems that neither side had fully anticipated at the outset of the conflict.6 Ukraine’s production target for 2025 is 4.5 million drones produced from Ukrainian factories alone, which is double their production from 2024, and slightly more production than what Russia is anticipated to produce by the end of 2025.7

How Much Warning Can a Person Receive Before a Drone’s Guns or Missiles Hit Their Target?

The distinct sound of an approaching drone (like the hum of swarming hornets) has become an ominous signal of imminent danger that those familiar with the trenches of Ukraine have likened to a “serious psychological attack.8” A volunteer group that builds FPV kamikaze drones (the “Wild Hornets” unit) for the Armed Forces of Ukraine reports that an FPV drone can travel in excess of 186 mph.9 Even, smaller FPV drones typically travel at 37 mph, which means that people cannot outrun a pursuing FPV platform.10

Large government and military drones, typically weighing over 150 kg, often operate at extremely high altitudes, with some surveillance platforms flying between 22,000 and 50,000 feet. At these elevations, they are virtually undetectable from the ground, since sound dissipates long before it reaches the surface, and visual identification is nearly impossible without advanced tracking systems. In contrast, smaller drones, such as microdrones (under 250 g) or small unmanned aerial systems (250 g–25 kg), tend to fly much lower, typically between 500 and 650 feet.11 These low-flying platforms are nearly silent and invisible above noisy battlefields, making them highly effective for reconnaissance or surprise attacks. However, drones delivering small munitions face limitations at higher altitudes, where gravity and wind introduce drift and reduce precision. To strike accurately, drones must descend to within 10–30 yards of their target, at which point their sound and movement may be detectable, giving soldiers a fleeting chance to react or defend themselves. The main warning sign of approaching danger is a change in the drone’s sound. As its sound intensifies, the drone is initiating an attack.

How Do Drone Attacks Differ From Other Methods Used in War?

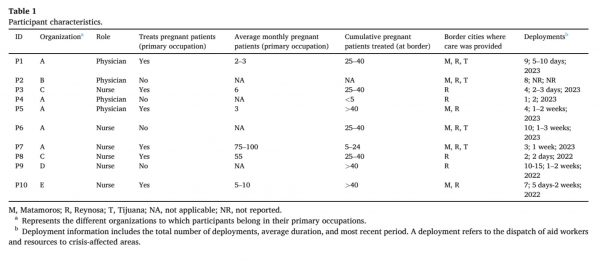

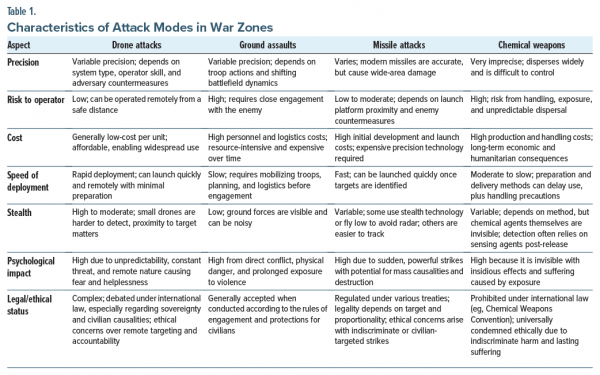

Table 1 compares the characteristics of drones (eg, which deliver rapid and highly precise and inexpensive attacks under the direction of an operator who may be miles away) with other attack modes used in war zones.

How Does the Threat of a Drone Attack Induce Psychological Distress and Interfere With Normal Functioning?

Mr A’s experience illustrates the unpredictable nature of drone attacks and the helplessness they can instill in soldiers. Without hearing or seeing the drone, Mr A sustained a catastrophic injury and was subjected to what can only be described as a remote-controlled execution, which was filmed, shared, and consumed on social media by a distant, opinionated audience. This convergence of battlefield lethality and digital dissemination represents a novel dimension of modern warfare, with unique implications for psychological trauma, moral injury, and clinical care that we have yet to fully understand.

Experiencing a drone attack is a distressing and unforgettable event. The sound of a drone can evoke significant anxiety, especially in places like Ukraine where trading the front lines for the home front does not stop drone attacks. Some Ukrainian clinicians have started referring to the drone attack–related clinical presentations they are seeing as “dronophobia” due to the unique hypervigilance behavior with corresponding hyperarousal and avoidance behaviors.8 For those who operate drones or have become accustomed to enemy drone activity, their anxiety may diminish as the sounds become more familiar. However, for many citizen soldiers and battle-hardened service members, the ongoing threat of drone attacks contributes to persistent hypervigilance and hyperarousal. Although drones have become a defining feature of modern warfare, we still know little about their psychological impact. Much of what we now recognize as drone warfare has taken shape on the battlefields in Ukraine, where these systems have been used on an unprecedented scale since Russia’s full-scale invasion on February 22, 2022. Because the war in Ukraine is so recent, the long-term psychological sequelae, on both soldiers and civilians, are still unfolding. A Ukrainian psychiatrist forewarned that the United States’ benign use of drones for weddings and real estate could become deeply triggering in a postwar Ukraine. As with previous conflicts, such as those during the GWOT, the true human consequences often take years, sometimes decades, to fully emerge and be acknowledged. This case of Mr A offers a window into the psychological realities of a new kind of asymmetrical warfare.

Many Ukrainian service members report that being within 5–10 miles of the front, well within the active range of FPV drones, requires constant vigilance: listening for the distinct hum of approaching drones while continuously scanning the sky. To adapt to the ever-present threat of attack, soldiers seek cover; make short, abrupt movements when the sound of drones fade; scan for nearby cover; peek around corners before crossing open spaces; and look upward frequently. Their constant skyward scanning exposes added vulnerability to the dual threat of hidden ground mines. Many soldiers avoid wearing tactical headphones out of fear that they will not hear an approaching drone, and some refuse to ride in military vehicles, which were once considered safe but are now viewed as prime targets.

Relatives of soldiers who have experienced drone attacks often notice significant behavioral changes. Before drone anxiety took hold, soldiers on leave would brighten their homes by opening curtains. Now, hundreds of miles away from the front, they keep their windows covered and lights dimmed, with furniture pushed to the edges of rooms to allow for unobstructed movement. During air raid sirens, while families seek shelter, these soldiers scan the skies from windows. Even simple activities, like walking outdoors with their children, are accompanied by upward glances. These behaviors reflect a durable state of hypervigilance: survival instincts and habits deeply ingrained by frontline experience and reinforced by the country’s persistent threat of drone attacks. This constant, looming danger makes it difficult for such adaptations to fade, even in relative safety.

Where Can a Person Feel Safe From the Threat of Drone Attacks?

Based on our Ukrainian coauthors’ experience treating service members, a sense of safety comes from minimizing exposure to open and vulnerable spaces. Many soldiers and civilians avoid windows, which mirrors their frontline behavior. On the battlefield, the most dangerous location is a dugout without overhead cover; soldiers prefer trenches with roofs or some form of overhead protection.

When away from the front, soldiers often seek windowless rooms or shelter in basements (ie, spaces that provide a greater sense of security against drone threats). Similarly, civilians find refuge underground (eg, in parking garages, subway stations, or basements). During a visit by Home Base clinicians to Ukraine, a “two-wall” shelter-in-place guideline was recommended to maximize protection. Many Ukrainians relocated from heavily targeted urban centers to private country homes, seeking distance not only from drone attacks but also from the psychological strain of continuous urban bombardment.

Who Is Most Susceptible to the Psychological Sequelae of Recent or Imminent Drone Attacks?

While real-world training and tactical preparation enhance a soldier’s ability to respond to the threat of a drone attack, the current reality is this knowledge offers limited protection against the stealth and precision of modern drone warfare. The persistent presence of drones can generate chronic psychological stress, and many soldiers report heightened anxiety, even when no immediate threat is apparent. Civilian soldiers, which is what most of Ukraine’s soldiers are, who are predisposed to anxiety, phobias, and distrust or who lack effective coping mechanisms are being found to be particularly susceptible to severe psychological distress from the threat of drone strikes.

Individuals who have experienced a drone strike, particularly those injured by one, are at heightened risk for developing persistent psychological symptoms, a vulnerability intensified by the ongoing threat of repeated attacks. For affected Ukrainian soldiers, the high likelihood of returning to active duty further increases their exposure to combat stressors. Likewise, the scale of Russian drone strikes on Ukrainian cities and towns raises concern that the broader civilian population faces an elevated risk of drone-related psychological symptoms.12

What Types of Physical and Psychological Symptoms Can Arise in the Context of Drone Attacks?

Hospitalized military personnel often develop psychological symptoms of posttraumatic stress (eg, with intrusive symptoms, avoidance behavior, and psychophysiological arousal) and anxiety disorders (eg, panic attacks, phobic reactions) following drone strikes. Substance use (involving alcohol and other psychoactive substances) is frequent among those who have been exposed to a drone attack, particularly those on the front or returning to the front where a high probability of re-exposure exists. Sleep disturbances (especially insomnia and nightmares) are common, with those attacked during dusk or at nighttime reporting heightened distress. The impact of such trauma can be stubbornly durable, especially in a country with permeable front lines, significantly impacting mental health and overall well-being.13

What Happened to Mr A?

Mr A experienced intense combat-related stress resulting from repeated battlefield drone attacks. Following evacuation, he was treated across 6 different medical facilities and underwent multiple surgical interventions, including bilateral lower limb amputations. Due to his fragmented care, brief hospitalizations, and lack of coordinated psychological support, Mr A was unable to initiate a structured rehabilitation process. Consequently, symptoms of acute stress disorder progressed, and he met diagnostic criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

His anxiety significantly interfered with daily functioning. Mr A mitigated perceived threats by moving his bed away from windows, keeping his curtains drawn, maintaining all personal electronic devices in a ready state, and keeping the lights dimmed. Exposure to drone-like auditory stimuli triggered intense fear, anxiety, and feelings of helplessness.

Five months after his drone attack, Mr A was admitted to a specialized psychiatric polytrauma center that provided a multidisciplinary, integrative treatment protocol. His psychopharmacologic regimen included duloxetine (initiated at 30 mg/day and titrated to 60 mg/day), pregabalin (600 mg/day, tapered to 150 mg/day), quetiapine (100 mg/day), and carbamazepine (200 mg/day). These medications were complemented by multimodal therapeutic interventions, including individual evidence-based therapy (cognitive-behavioral therapy and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing); virtual reality for pain relief; group therapy; active sports (such as swimming); art therapy; ecotherapy; yoga; and acupuncture.

By the time of his discharge, Mr A’s symptoms improved sufficiently, and he no longer met diagnostic criteria for PTSD. Nonetheless, he continued to experience subthreshold generalized anxiety and a marked fear of drones, particularly during early morning hours.

CONCLUSION

The widespread use of drone platforms is largely attributable to their low operational cost, ease of use, and high mobility. These characteristics render drones particularly effective for high-risk military applications that mitigate operator exposure to danger while maximizing lethality against adversaries.

With the increasing prevalence of drone attacks, the distinct hum of an approaching drone, often likened to the swarming of hornets, has itself become a psychological weapon. The escalating pitch signals an imminent threat, which elicits fear and helplessness even before an attack. Whether directly experienced or witnessed in the aftermath, the auditory stimulus leaves a durable psychological imprint, with effects that may extend across generations, especially in conflict zones like Ukraine, where civilians endure repeated strikes that blur the boundaries between the front lines and the home front.

Addressing the psychological and societal consequences of drone warfare necessitates a comprehensive, integrated, multidisciplinary strategy.

As lessons from the GWOT have shown, this approach should integrate immediate medical care, ongoing mental health support that incorporates family, sustained surveillance, and community-based programs to mitigate the lasting impact of conflict, which is essential to address the consequences of war and the prolonged psychological and societal sequelae of drone attacks.14–16

Published Online: November 6, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25f04056

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: August 12, 2025; accepted September 25, 2025.

To Cite: Bonvie JL, Matta SE, Andriichenko S, et al. Psychological sequelae of drone attacks. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(6):25f04056.

Author Affiliations: Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts (Bonvie, Matta, Stern); Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts (Bonvie, Matta, Stern); Center for Psychiatric Care and Professional Psychophysiological Selection of the State Institution, Kyiv, Ukraine (Andriichenko); Medical and Psychological Rehabilitation of the Medical Center, Novi Sanzhary, Ukraine (Slobodian); Global Response Medicine, Marco Island, Florida (Leiner); Defend, Aid, Widen, Future (DAWN), Hillsboro, Oregon (Brockdorf).

Bonvie, Matta, Andriichenko, Slobodian, Leiner, and Brockdorf are co-first authors; Stern is the senior author.

Corresponding Author: Joseph L. Bonvie, PsyD, One Constitution Road, Suite 140, Charlestown, MA 02129 ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to extend their sincere thanks to the Ukrainian Ministry of Interior and the dedicated clinicians who made this case vignette possible. As drone warfare continues to reshape the landscape of modern conflict, the mental and physical toll it exacts remains underexplored in the literature. This case offers a timely and important contribution to that emerging conversation.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Government, the Department of Defense or the Department of Veterans Affairs. The case vignette is based on the experience of a real soldier who was treated at the Department of Psychosomatic Pathology, Territorial Medical Association, Ministry of Internal Affairs of Ukraine, in Kyiv. Due to ongoing hostilities in Ukraine, certain details have been altered to protect his identity and his unit.

Clinical Points

- First-person view drones provide a cost-effective means of delivering targeted strikes, with user-friendly controls that allow operators of varying skill levels to rapidly acquire piloting proficiency and conduct missions from a wide range of distances.

- The sound of a drone often triggers intense anxiety, even when military personnel and civilians are far from the front lines.

- The ever-present specter of drone attacks in war-torn nations forces soldiers and civilians to become hypervigilant.

- Those who have experienced a drone strike, especially those who have been injured, are especially vulnerable to developing intense short-term and long-term psychological sequelae that are compounded by the ongoing threat of repeated attacks.

- Optimal management of the sequelae of drone attacks involves a comprehensive, integrated approach to address immediate and long-term physical and psychological sequelae.

References (16)

- Home Base. Home Base and Global Response Medicine launch “Invisible Wounds of Ukraine” initiative to support Ukrainian service members, veterans, families, and medical professionals. 2025. Accessed August 12, 2025. https://homebase.org/press-invisible-wounds-of-ukraine/

- Sprotyvg7.com.ua. Demonstrator of promising mirrors of armor and explosive techniques for explosive development. 2025. Accessed August 12, 2025. https://sprotyvg7.com.ua/lesson/dovidnik-perspektivnix-zrazkiv-ozbroyennya-ta-vijskovoi-texniki-dlya-rozviduvalnix-pidrozdiliv

- Bendett S, Kirichenko D. Battlefield drones and the accelerating autonomous arms race in Ukraine. Modern War Institute; 2025. Accessed August 12, 2025. https://mwi.westpoint.edu/battlefield-drones-and-the-accelerating-autonomous-arms-race-in-ukraine/

- Ibrahim A. Employment of FPV Drones in Russia-Ukraine war: Lessons and Future Outlook. Modern Diplomacy. 2024. Accessed August 12, 2025. https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2024/12/14/employment-of-fpv-drones-in-russia-ukraine-war-lessons-and-future-outlook/

- Käihkö I, Honig JW. Ukraine’s not-so-whole-of-society at war: force generation in modern developed societies. Parameters. 2025;55(1).

- Kullab S. How Ukraine soldiers use inexpensive commercial drones on the battlefield. PBS NewsHour; 2023. Accessed August 12, 2025. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/how-ukraine-soldiers-use-inexpensive-commercial-drones-on-the-battlefield

- Axe D. 4.5 Million Drones Is A Lot drones. It’s Ukraine’s New Production Target 2025. Forbes; 2025. Accessed August 12, 2025. https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidaxe/2025/03/12/45-million-drones-is-a-lot-of-drones-its-ukraines-new-production-target-for-2025/

- Gunter J. They escaped Ukraine’s front lines. The sound of drones followed them. BBC News; 2025. Accessed August 12, 2025. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c23gjk7dlvlo

- Struck J. “Can chase a helicopter” – Ukrainian FPV drone reaches 325 km/h. Kyiv Post; 2024. Accessed August 12, 2025. https://www.kyivpost.com/post/39057

- Sauer P. “It is impossible to outrun them”: How drones transformed war in Ukraine. The Guardian; 2025. Accessed August 12, 2025. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/jan/04/it-is-impossible-to-outrun-them-how-drones-transformed-war-in-ukraine

- JOUAV. Different Types of Drones and Uses (2025 Full Guide). Jouav; 2025. https://www.jouav.com/blog/drone-types.html

- Naeem A, Sikder I, Wang S, et al. Parent-child mental health in Ukraine in relation to war trauma and drone attacks. Compr Psychiatry. 2025;139:152590. PubMed CrossRef

- Sak L, Khaustova O. Understanding somatic comorbidity: Impacts of combat and stress factors on the complexity of military trauma [conference presentation]. In: Matta SE, Leister M, Caujolle-Alls K, et al. Research Institute of Mental Health, Bogomolets National Medical University; 2024. In: War in Ukraine: Assessing the Global Consequences. European Association for Psychosomatic Medicine. https://eapm.eu.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/EAPM2024_ProgramV_FS-nm-240408.pdf.

- Dieterich-Hartwell R, Brodovsky J, DeAlba K, et al. An integrative, holistic treatment approach for veterans with chronic traumatic brain injury and associated comorbidities: case report. Front Psychiatry. 2025;16:1568876. PubMed CrossRef

- Hoover GG, Teer A, Lento R, et al. Innovative outpatient treatment for veterans and service members and their family members. Front Psychiatry. 2024;15:1377433. PubMed CrossRef

- Harward LK, Lento RM, Teer A, et al. Massed treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder, traumatic brain injury, and co-occurring conditions: the Home Base intensive outpatient program for military veterans and service members. Front Psychiatry. 2024;15:1387186. PubMed CrossRef